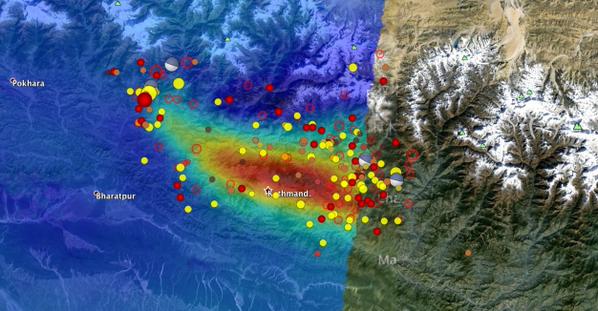

On April 25, 2015, just before midday local time, the Nepalese Himalayas was struck by an earthquake of magnitude ≥ 7.8. Its epicentral region was located about 80km west of Kathmandu, but the many aftershocks have been clustered around the Valley, shifting an entire region. At least ten thousand lives were lost or injured as a result. This horrific calamity was not caused by divine retribution, but rather by collisions occurring, with some predictability, between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. Several M ≥ 5 aftershocks are expected, with a greater than 50% chance of an M ≥ 6 aftershock, in the coming months (Source: USGS).

Such widely felt effects, together with the increasing pervasion of social media, are generating an unprecedented flow of data. Making sense of it is difficult for people in the midst of the crisis, let alone those on the outside — though there are some worthy efforts (*). Many call for more aid, but some say there is too much. On live television, it seems to be business as usual in the Kathmandu Valley. However, the normality orchestrated on TV reveals nothing of the disruptions likely to come: critical shortages of manpower, water, fuel and electricity, failures of agriculture and transport, debilitated families, missionary predation, ever-growing dependence on foreigners.

The situation in the Valley — since it’s what I know, it’s the part I can assess — now seems to be as follows. In the Durbar Square of Lalitpur, the Jagannarayan and Hari Shankar temples have fully collapsed. Hiraṇyavarṇa-mahāvihāra, the Golden Temple, is undamaged. There is widespread damage in Bungamati, with Amarāvati-mahāvihāra mandir laid waste. The chariot of Karuṇāmaya (‘Macchendranath’), now on its twelve-year yātrā, has been hit. In Kathmandu Durbar square, Kasthamandap, Maju Dega, Kam Dev temple and Trailokya Mohan Narayan temple were destroyed; the Kumari House stands unaffected. Kalmochan temple at Thapathali and Bhimsen Tower, a.k.a. Dharahara, have fallen down. The Swayambhu caitya has not been obviously affected, though some surrounding buildings, including the Pratappur temple, are shattered. Although a hairline crack has appeared in the Bodhnath stūpa it remains intact, apart from a collapsed stūpa on its periphery (misleadingly photographed in front of the main structure).

The old cities of Bhaktapur, Sankhu, Kirtipur and Khokana have suffered severe damage and loss of life. Beyond the Valley, in Gorkha, Sindhupalchowk and Nuwakot, whole villages have been wiped out, and reportedly, hundreds of thousands are affected in the Tibet Autonomous Region. It looks like the communities at these places will receive some aid from outside, sooner or later. Whether it arrives in good time, reaches the people who need it, is usable, makes things better rather than worse — or is needed at all — are altogether different questions.

Today nobody knows how much is being stolen from heritage sites. While UNESCO has funds to hire security, and jurisdiction over the entire Valley, the Kathmandu office says it can only work on its database. Fortunately, the job is somehow getting done. The false opposition ‘protect lives, not buildings’ is also getting a lot of airtime. Buildings are there to improve lives (unless built in a failing state). That’s why the displaced people who shivered under tarpaulins for a while have gone back to their homes as fast as they can, in spite of the risks.

The proposition that traditional spaces merely “serve as an anchor for aspiration and memory” and have nothing to do with livelihoods, shelter, storage, commerce, discourse, traffic, and the experience of pleasure and meaning is very mistaken. This damning with faint praise is no ordinary lapse of judgment; the Newars’ spaces seem to incite real unease among those who don’t belong there. This shows that they work as intended, and that their value comprises far more than the sum of their parts. Even in times of weakness, the Kathmandu Valley’s precious urban landscape can resist the neuroses projected onto it from outside. Nonetheless,this priceless quality won’t continue of its own accord. It needs intelligence, attention and work. That is how lives are renewed.