尼玛但增 (主编) 《罗布林卡珍藏文物辑选》 中国藏学出版社, 2011.

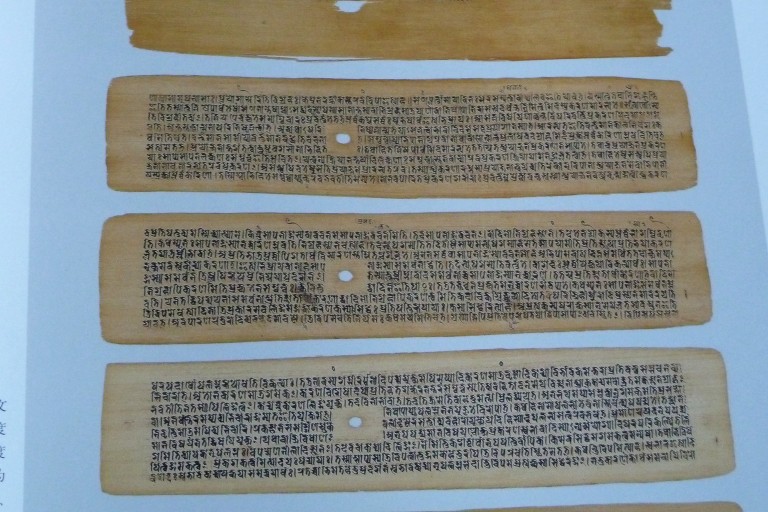

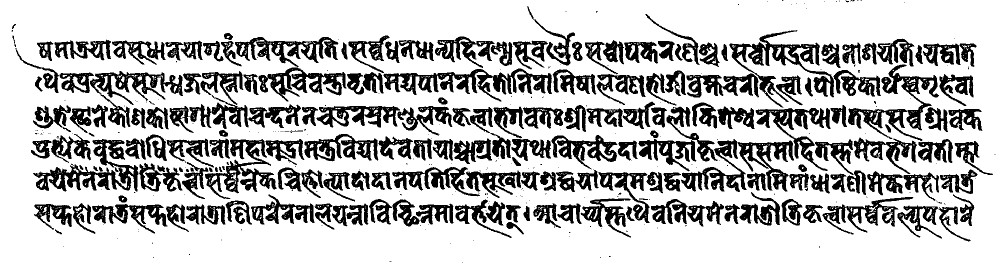

A Newar-copied pramāṇa manuscript? You don’t see those every day—especially in Nepal.

Anshuman Pandey. ‘Proposal to Encode the Siddham Script in ISO/IEC 10646’.

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4294 L2/12-234R. PDF. 2012/08/01.

Mr. Pandey’s proposal – now no longer preliminary – promises to fill yet another gaping hole in the standard encoding of important Indic scripts. Now would be an appropriate time to comment, if you haven’t already commented.

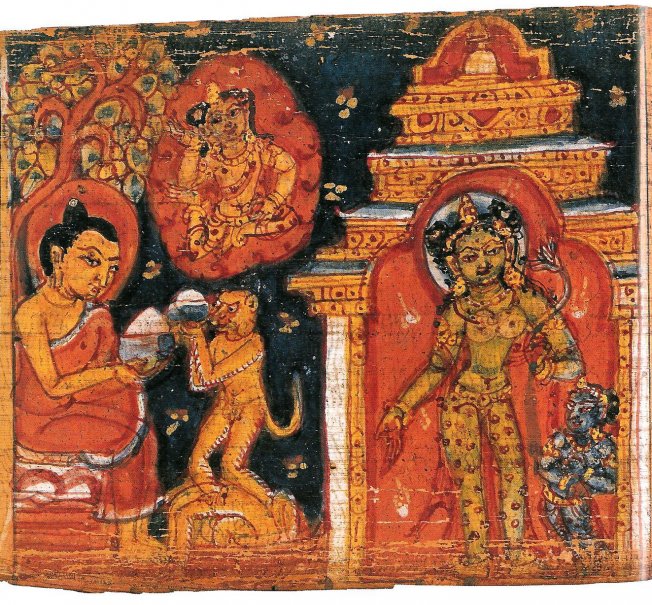

(I would hope, at minimum, for the addition of a full set of ten digits in the final proposal. Often such basics fall through the gaps because the corpus of readily available primary material is so limited. Here‘s a nice “7-8th century” bilingual manuscript with a varṇamālā (no digits, though) which is both in good condition and readable online, thanks to the care of its Japanese custodians. Incidentally, this clearly confirms that two of the “Punctuation and ornaments” in Pandey’s Fig. 33 are ornamental final anusvāra [अं字].)

Comments should be emailed to Anshuman Pandey, whose address is given in the N4294 proposal (link above) and at the bottom of his personal website (link).

Guess what, theists? Animals have feelings too. That’s what Cambridge scientists are now confident in saying in the wake of the recent Francis Crick Conference. Science and reason are important in a modern society, so it just became that much harder to inflict scripturally sanctioned harm on sentient beings.

This reminds me of a discussion I once had in Germany. Prof. Schmithausen, you were right to think that something was up with theistic contempt for animals. The priests you knew may have been accurate on the detail – animals don’t have souls – but they were wrong on the big picture: they don’t either. Both humans and animals have “homologous subcortical brain networks” and share “primal affective qualia”. Every body hurts; and that suppressed observation was obvious long before it became a hipster anthem.

Long-time readers might remember this – now in print:

Long-time readers might remember this – now in print:

Yoshizaki, Kazumi (吉崎一美). The Kathmandu Valley as a Water Pot: Abstracts of research papers on Newar Buddhism in Nepal. Kathmandu: Vajra Books, 2012. 172 pp. ISBN: 9937506743. EAN: 9789937506748. USD$12.95. [official site]

[See Yoshizaki (1991), (1994a), (1994b), (1995), (1996a), (1996b), (1996c), (1997a), (1997b), (1997c), (1998a), (1998b), (1998c), (1998d), (1999), (2001), (2002a), (2002b), (2003a), (2003b), (2005a), (2005b), (2005c), (2007a) and several others.]

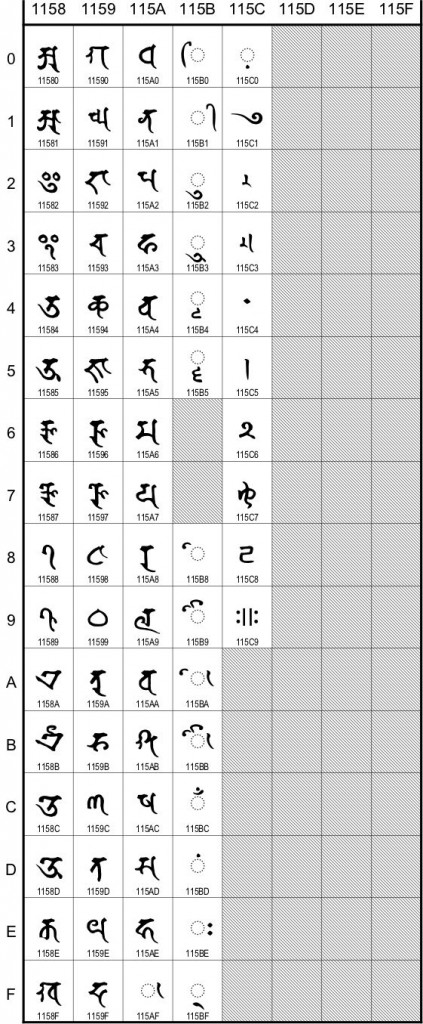

Refer to: Anshuman Pandey, ‘N4184 Proposal to Encode the Newar Script in ISO/IEC 10646’, February 29, 2012 [PDF]. Previous discussion: here.

The name ‘Newar’ is preferable simply because most other options can be ruled out. ‘Nepalese’ is untenable, because it falsely implies a one-to-one relationship with the present-day nation-state, even though it is accurate within a certain (historically earlier) context. ‘Newari’ is a (now deprecated) name for the language – not the script, nor anything else; ‘Nevārī’ is quite meaningless, except to some Indologists.

The proposal, as I understand it, indeed deals with the Pracalita script, but has enough hooks to allow unification with proposals for other Newar scripts, such as Bhujiṅmola – hence ‘Newar’. (NB: It is not yet clear whether unification with Rañjanā – which is, strictly speaking, Indo-Nepalese, and which has a user base that includes many non-Newars, such as Tibetans – is feasible. In any case, much of the present and previous discussion about the Pracalita script is also applicable to Rañjanā.)

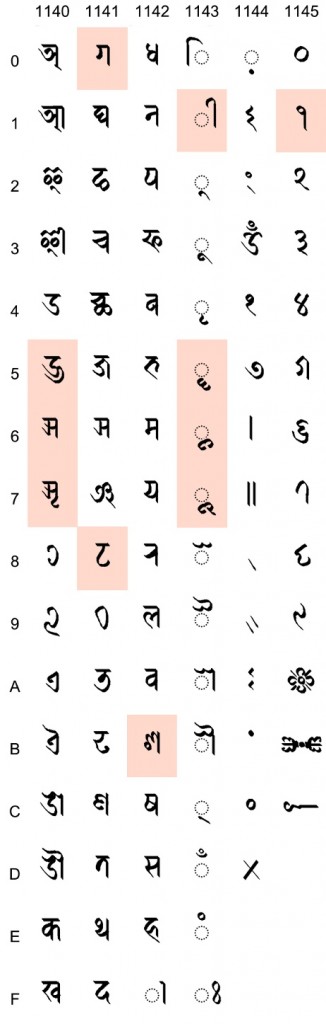

11442 NEWAR FINAL ANUSVARA: Although this mark originates with the m-virāma mark used by East Indian scribes, in Nepal it has multivalent significance and in many contexts has nothing to do with nasalization (often being interchangeable with 1144B NEWAR GAP FILLER). Recommendation: Minimise phonetic/semantic description in favour of graphic description – maybe NEWAR SEMICOLON for want of a better term. Classify under Punctuation or Various Signs.

11443 NEWAR SIDDHI = शुभचिं (Shrestha NS 1132:21). There is no uniform name for this mark in Newar (esp. not the neologism bhiṃciṃ), nor is siddhi/añji recommended (not just because this designation is unknown in Nepal, but because usage may also vary; confusion with NEWAR OM is common). Recommendation: NEWAR AUSPICIOUSNESS MARK or similar.

11448 NEWAR COMMA = अर्धविराम (Shrestha NS 1132:24).

11449 NEWAR DOUBLE COMMA: I now think this mark can be represented with two adjacent NEWAR COMMAs. Its usual behaviour of stacking diagonally (see Fig.3) rather than horizontally should however be specified. Recommendation: Remove from the repertoire.

1144B NEWAR HIGH SPACING DOT = अल्पविराम (ibid.).

1144C NEWAR ABBREVIATION SIGN CIRCLE = संक्षेपीकरण यानाः च्वयातःगु थासय् थुगु चिं (ibid.).

1145A NEWAR FLOWER = स्वांथें ज्याःगु चिं (ibid.).

1145C NEWAR PLACEHOLDER MARK is the line-width equivalent of the NEWAR GAP FILLER (see below). Recommendation: Change name to NEWAR LINE FILLER MARK.

Following comments on earlier drafts of N4184, especially those of Kashinath Tamot, it should be clarified that the primary function of 1144B NEWAR GAP FILLER is not that of indicating a break in a word (as per the previous name SANDHI MARK), but rather of filling space up to the end of a line margin. (A hyphen indeed performs a space-filling operation as well as functioning as a word-breaking mark. However, I suggest that ‘hyphenation’ be dropped from the formal description of this mark to avoid confusion.)

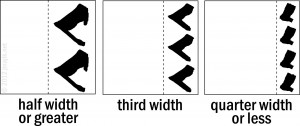

The purpose of this mark has been obvious enough to specialists – recently see, e.g. Ishida (2011:ix), where it is called a ‘line-filler character’, Zeilenfüllzeichen. (In fact, this mark does not fill a line – this is the function of 1145C NEWAR PLACEHOLDER MARK; rather, it fills a space of less than one full glyph-width at the end of a margin, not necessarily the end of a line.) Nonetheless, it is easily seen that the mark could be confused with, e.g., a visarga, daṇḍa or similar. In earlier discussion on the proposal, its purpose has remained unclear to the user community, perhaps due to its unstable shape. Significantly, the NEWAR GAP FILLER MARK changes according to the width of the glyph. Its behaviour may be represented as follows:

Variations in this mark may therefore be regarded as contextual alternatives, rather than separate code points. I suggest, as per the diagram, that no more than three variants need be represented; although the glyph could conceivably incorporate four or more variations (e.g., five vertically stacked dots, at 20% character width), this is probably excessive.

Recommendation: It may be implemented as one code point with contextual alternates, or 3 or more code points corresponding to each quantum of width.

Several glyphs may be alternatively represented with swash forms, created by extending elements of the glyph into surrounding white space. These forms do not require dedicated representation in an encoded repertoire; however, they should be included in any full description of Indo-Newar scribal culture, and font designers might want to incorporate them. Swash forms are often contextually invoked: they are used at the top line of a block of text (upward extension), but may also be seen on the bottom line (downward extension), and even more rarely at the right and left margins, and within interlinear white space. An example:

Characters routinely represented as swash forms include:

11432 NEWAR VOWEL SIGN U, 11433 NEWAR VOWEL SIGN UU, 11439 NEWAR VOWEL SIGN AI, 1143B NEWAR VOWEL SIGN AU, (superscribed) 11428 NEWAR LETTER RA, 1143D NEWAR SIGN CANDRABINDU, 1143E NEWAR SIGN ANUSVARA – upward extension;11402 NEWAR LETTER I, 11403 NEWAR LETTER II, (subscribed) 11417 NEWAR LETTER NYA, 1141D NEWAR LETTER TA, 11423 NEWAR LETTER PHA, 11425 NEWAR LETTER BHA, 11429 NEWAR LETTER LA, 1142D NEWAR LETTER SA, 1142E NEWAR LETTER HA, 1143C NEWAR SIGN VIRAMA – downward extension.The following changes to standard forms are recommended – see glyphs highlighted in Fig.3, in which all glyphs have been redrawn from scratch to accord with common scribal practice. The most widespread change is that the headstroke no longer extends past the right descender (which is inconsistent with almost all scribal practice). Standard forms for VOCALIC R, VOCALIC RR, GA, SHA, dependent VOWEL SIGN II, VOCALIC R, VOCALIC RR as well as *VOCALIC L, VOCALIC LL (these should certainly be specified and named) should be altered accordingly. DIGIT ONE should also be changed in order to avoid confusion with SIDDHI.

5.2 Letter-Numerals: “There are at least 27 such Newar ‘letter numerals’… It may be possible to unify Newar letter-numbers with corresponding Brahmi characters.” The issue here, as far as I can see, is: which letter-numeral conjuncts differ from non-numeral conjuncts of the same letters (all differences should be specified). To put it another way: which letter-numeral conjuncts uniquely signify letter numerals, if any? Perhaps our European colleagues, with their extensive access to funding, institutional support and manuscript sources, could clarify the matter. (Don’t worry, we won’t hold our breath.)

5.3 “Should editorial marks be encoded on a per script basis or would be it reasonable to unify such marks in a pan-Indic block?” (Pandey 2012:13). Out of our hands, but if they aren’t unified, they should be included in the Newar block.

[rev 0.1: 2012/06/19]

Marina Toumpouri [academia.edu]. ‘L’illustration byzantine du Roman de Barlaam et Joasaph’. 3 vols., 792 pp. PhD diss., Université Charles de Gaulle (Lille), 2010.

A worthy study of some real Western Buddhism:

The Barlaam and Joasaph tale is a text of Buddhist inspiration which tells the story of the son of an Indian king, Joasaph, who, tired of mundane pleasures, is converted by the monk Barlaam and eventually becomes a monk. The Greek version of the Barlaam and Joasaph Romance, the work of Euthyme the Athonite (+1028), monk of Georgian origin, is datable between 975 and 987. The text is known to us in hundred and fifty nine manuscripts, among which six were illustrated, produced between the eleventh and the sixteenth century. The present work is dedicated to the study of the illustrated manuscripts.

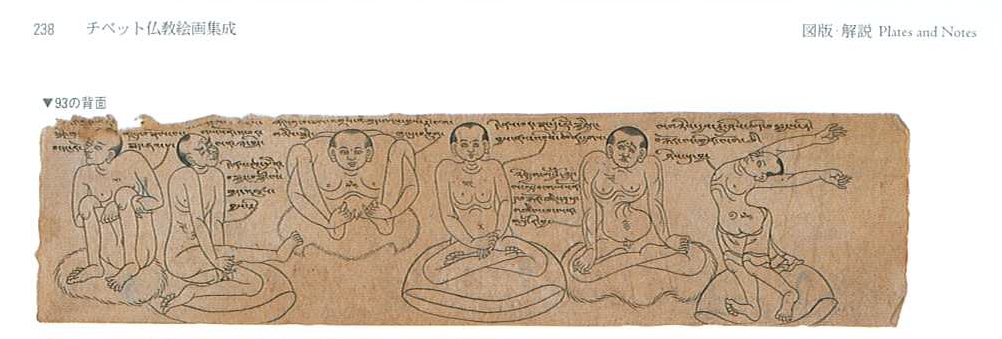

田中公明 『チベット仏敎絵画集成 : タンカの芸術 ハンビッツ文化財団蔵』 第6卷 臨川書店; ハンビッツ文化財団 15,750円

Tanaka, Kimiaki (ed.), Rolf W. Giebel (tr.) Art of Thangka: From the Hahn Kwang-ho Collection. Volume 6. Kyoto/Seoul: Rinsen Book Co. & The Hahn Cultural Foundation, 2012. 266 pp. ISBN-13: 978-4653041245 [amazon.jp / rakuten.co.jp]

Gudrun Bühnemann. The Life of the Buddha: Buddhist and Śaiva Iconography and Visual Narratives in Artists’ Sketchbooks from Nepal. By Gudrun Bühnemann, with Transliterations and Translations from the Newari by Kashinath Tamot. Lumbini: Lumbini International Research Institute, 2012. ISBN 9789937553049, 204 pp. USD$50. [available from Vajra Books]

This book describes, analyses and reproduces line drawings from two manuscripts and a related section from a third manuscript. These are: 1) Manuscript M.82.169.2, preserved in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (circa late nineteenth century) 2) Manuscript 82.242.1-24, preserved in the Newark Museum (from the later part of the twentieth century) and 3) A section from manuscript 440 in the private collection of Ian Alsop, Santa Fe, New Mexico (early twentieth century). The line drawings depict Hindu/Śaiva and Buddhist deities and themes, but the Buddhist material is predominant, as one would expect in artists’ sketchbooks from Patan. […]

The Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente (IsIAO), standard bearer of the scholastic brilliance incarnated in Giuseppe Tucci, co-founder of its predecessor institution, is a walking ghost. Its liquidation has already been decreed. But this is a ghost that will not go quietly. Let me satiate the preta by linking to its disembodied voice: isiaoghost.wordpress.com.

A stupid person is a person who caused losses to another person or to a group of persons while himself deriving no gain and even possibly incurring losses.

It doesn’t take much imagination to see that this is directed at the bureaucrats who sacrificed Tucci’s and Gnoli’s legacy upon the unholy altar of economic irrationality. Come to think of it, though, it could equally apply to certain academics. “It is not difficult to understand how […] institutional power enhances the damaging potential of a stupid person,” Prof. Cipolla observes. How true!

(Thanks to A. for the pointer.)