In recent years, Gregory Schopen has done more than anyone to force a reality check on the West’s part-idealized, part-fantasized conception of the Buddhist bhikṣu. Going boldly into vinaya texts that no Buddhist Studies scholar has read before, Schopen finds that the image of monks as world-renouncing ascetics is far removed from the evidence available in these codes.

Monks in India, certainly those affiliated with the Mūlasarvāstivāda, are seen to be entangled with the world as owners, inheritors, and leasers of property; as active seekers of sponsorship for the fabrication of monasteries and images; and as individuals who very much retain their caste and family identities. Rules for performing ‘meditation’ are comparatively thin; in one passage, those who go to the forest to meditate are denigrated as slightly strange in the head. Indian monastics are, in short, anticipated to be doing the things that Newar Buddhists were long accused of doing as “debasements” of monasticism — activities which, we now know, fall within the normal spectrum of behaviour mandated for the Indian tradition.

The most common objection to Schopen’s work has been that the vinaya itself represents an idealization. But this is his very point: it is remarkable that such prescriptions, laden with provisions for a monk’s immersion in mundane business and social affairs, represent the way things are supposed to be done. Nor should these codes be regarded as something which just sit out there in the realm of the ideal: they are indeed binding, written for the purpose of being binding, on their adherents; and in governing the operation of a saṅgha, their word is final.

A contribution published not long ago in the JPTS, by Peter Skilling,* unearths an extreme example of the monk mired in profanity: a ritual for the bhikṣu to magically reanimate a corpse and dispatch it to kill his foe. In the selected passage from the Vinayavibhaṅga (now preserved only in Tibetan and Chinese) the monk is a necromantic performer and would-be murderer by proxy, in a rite that entails:

- the monk going to a charnel ground at a suitable time;

- finding a suitable corpse;

- preparing it with unguents and so on;

- reanimating the corpse by possessing it with a vetāḍa/vetāla spirit,** invoked by means of an (unspecified) mantra;

- sending the zombie off, sword in hand, to kill a named victim, which it does, unless

- the zombie turns on the monk and kills him instead.

As Mr. Skilling observes, with his characteristic good humour and learning (qualities not often found in abundance, much less together, in the Pali Buddhist Studies community), “The primary concern of our text is not the ethics of the matter as such, but what sort of infringements of the monastic rules might be involved” (p.315). If the monk is killed by his own zombie, “the monk incurs a heavy fault (sthūlātyaya)… I do not know whether there are any other cases of posthumous penalties in the monastic codes, but here we have at least one”. That such an outcome was definitely anticipated by the redactors of the vinaya is reflected in the long list of protective techniques provided within the ritual.

Among those defensive options available to the monk is the recitation of a number of “the great apotropaic classics of early Buddhism — notably the Dhvajāgra, the Āṭānāṭīya-, and the Mahāsamāja-sūtras”. Skilling adds, “We still know very little about how the Mahāsūtras were actually used as a set, or to what degree the rituals may have corresponded to [Theravādin rites or] the Rakṣā rituals of Nepal” (p.314). In the literature of Indo-Newar Buddhism there are, in this case as in so many others, more than a few indications to be found regarding the actual practice of such rites.

The Mṛtyuvañcanopadeśa*** of Vāgīśvārakīrti, an Indian master who played an important role in the formation of Newar Buddhism, is a work dealing with the prolongation of one’s life. Although it is concerned primarily with tantric methods such as subtle yoga, it is remarkable that Vāgīśvārakīrti also advocates the recitation of these same Mahāsūtras for the purposes of increasing longevity. This throwback to a much earlier era of monastic practice in a c.11th-century text incidentally marks its author as a monk, or one who at the very least is strongly enculturated in monastic convention.

Later, during the post-Indian period of Newar Buddhism, a number of Sanskrit works were composed on the mollification of life-threatening omens, usually framed as dialogues between Lokeśvara and Tārā. These works offer a kind of meta-protective solution: now one recites either the Pañcarakṣā, or the Mṛtyuvañcanopadeśa itself, in order to avert untimely incidents.

In Skilling’s reference to “the Rakṣā rituals of Nepal”, there is the apparent implication that the rites and literature of the Pañcarakṣā are primarily Nepalese. In fact both the constituent works/deities and the set of five belong to the pan-Indian tradition (the latter, for example, being known to Abhayākaragupta). Again, it would have been nice to see elements regarded as outside the Indian mainstream not being automatically, erroneously, relegated to the Nepalese periphery, where they can be excluded from consideration.

In any case, Peter Skilling’s article adds to the enormous body of scholarship showing that tantric Buddhism has its origins firmly within the monastic community. We do not find a trace of the “siddha” founders proposed by Ronald Davidson in the earliest and best evidence, as exemplified in this extract from the vinaya. Nor should we expect anything different for a tradition that was, right from the start, indeed up to the present, transmitted almost entirely by monks or in connection with monastic institutions, and which makes frequent reference to the practices and ideals of Buddhist monasticism.

* ‘Zombies and Half-Zombies: Mahāsūtras and Other Protective Measures’ The Journal of the Pali Text Society, Vol. XXIX (2007), pp. 313-30.

** We should distinguish between the possessing spirit, the vetāla, and the corpse in its possessed/zombified state, as per Somadeva Vasudeva, ‘Concerning vetālas I‘.

*** Johannes Schneider (ed. and tr.), Diss., München, 2006/7? [no details to hand].

This thesis examines two works (My Journey to Lhasa and Magic and Mystery in Tibet) by Alexandra David-Neel. […] Central to this study is an examination of a claim by His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama that David-Neel creates an “authentic” picture of Tibet. In order to do this the first chapter establishes a working definition of authenticity based on both Western philosophy and Vajrayana Buddhism. This project argues that the advanced meditation techniques practiced by Alexandra David-Neel allow her to access a transcendent self that is able to overcome the self/other dichotomy. It also discusses the ways in which abjection and limit experiences enhance this breakdown. Finally, this thesis examines the roles that gender and a near absence of female Tibetan voice play in complicating the problems of self, subjectivity, and authenticity within these texts.

This thesis examines two works (My Journey to Lhasa and Magic and Mystery in Tibet) by Alexandra David-Neel. […] Central to this study is an examination of a claim by His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama that David-Neel creates an “authentic” picture of Tibet. In order to do this the first chapter establishes a working definition of authenticity based on both Western philosophy and Vajrayana Buddhism. This project argues that the advanced meditation techniques practiced by Alexandra David-Neel allow her to access a transcendent self that is able to overcome the self/other dichotomy. It also discusses the ways in which abjection and limit experiences enhance this breakdown. Finally, this thesis examines the roles that gender and a near absence of female Tibetan voice play in complicating the problems of self, subjectivity, and authenticity within these texts.

Mori, Masahide. Indo mikkyō no girei sekai (The Rituals of Tantric Buddhism in India). Sekai Shisōsha, 2011, 340pp. ISBN 978-4-7907-1498-9. [

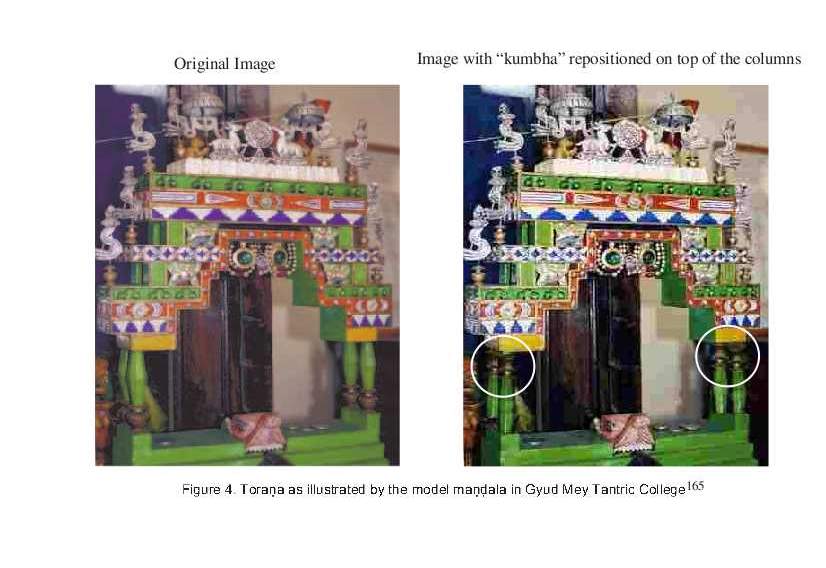

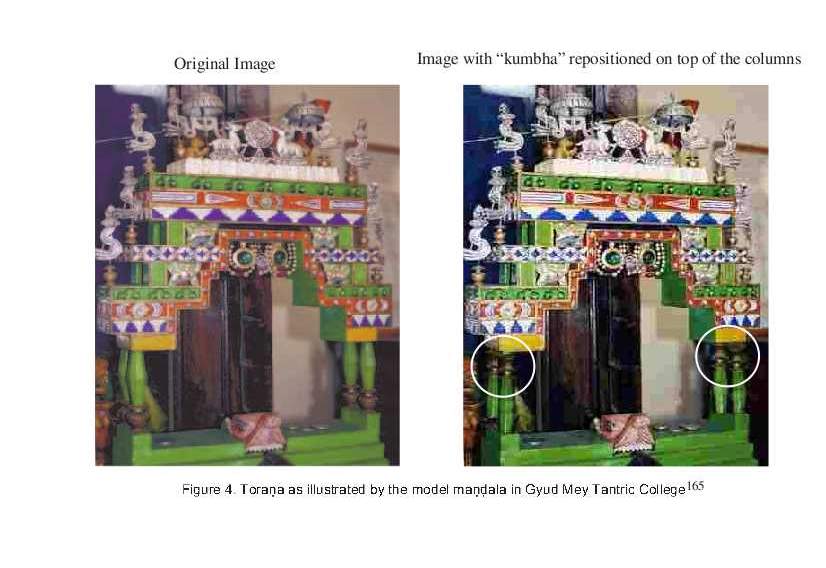

Mori, Masahide. Indo mikkyō no girei sekai (The Rituals of Tantric Buddhism in India). Sekai Shisōsha, 2011, 340pp. ISBN 978-4-7907-1498-9. [ Astrid Zotter and Christof Zotter (eds). Hindu and Buddhist initiations in India and Nepal. Ethno-Indology, v.10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2010. 380 p. ISBN 9783447063876. [

Astrid Zotter and Christof Zotter (eds). Hindu and Buddhist initiations in India and Nepal. Ethno-Indology, v.10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2010. 380 p. ISBN 9783447063876. [