Your comments are invited on a proposal to encode the script ‘prevalent’/’in vogue’ (pracalita) in Nepal since the late fourteenth century, and which since the Shah period has continued in use in the scribal and print culture of the Newars. The proposal under discussion was submitted a month ago by Anshuman Pandey to the international standards body for character sets, WG2 under JTC1 of the ISO. Download it here:

Anshuman Pandey. ‘Proposal to Encode the Newar Script in ISO/IEC 10646’. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 proposal N4184 [PDF]. January 5, 2012. [Supersedes N4038, ‘Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Prachalit Nepal Script’]

Anyone can submit a proposal for consideration by WG2. However, this is not a trivial process; documents need to comply with the group’s requirements, and if I observe correctly, there are very few competing complete proposals for historic scripts. No proposal has come from the Nepalese government, Newar culture having little, if any, official status in the Shah and post-Shah nation-state. The proposal under discussion (hereafter “N4184”) is that of a private individual, in collaboration with the Script Encoding Initiative at Berkeley. Mr. Pandey has graciously agreed to consider informed feedback on his proposal, which I hope will be incorporated into future documents submitted to WG2. It is in this constructive spirit that your feedback is requested; anyone may add comments via the form the end of this post.

1. Intended scope of these comments: focus on repertoire

The present discussion should focus on the completeness and accuracy of the glyph repertoire represented in the present proposal. Matters such as the proposed name and classification of the script, the description of interaction between glyphs (e.g. conjunct formation, §4.8.1), issues related to other Nepalese or Indic scripts (except where strictly relevant) and so on should notbe discussed here. If there is sufficient interest, these matters can be addressed in separate posting(s). Here I will offer some of my own preliminary, informal feedback on the proposal, on which comments are also welcome.

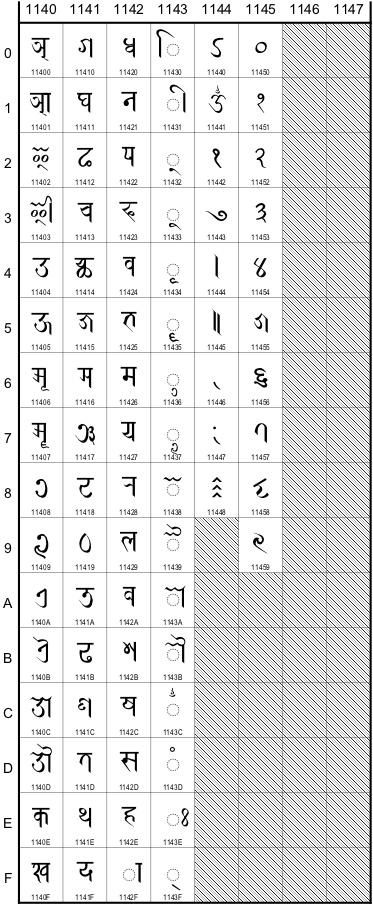

N4184 aims to “encode a core set of Newar characters” (p.17). This invites the question of how “core” should be defined. I will not discuss this in depth, other to say that the standard should include those characters which are most common and most useful in this form of writing. Specifically, I propose that the characters depicted in Figs.6 and 7 below should be part of the standard. This is the repertoire proposed in N4184:

2. Which form of the script is represented?

It is not clear which historical form of the script is represented in N4184. The so-called pracalita script, having been in use for several centuries, is known to vary under different periods and circumstances. But as no attempt has been made, to my knowledge, to describe this variation, there is no analysis that may guide standardization. However, this lack of a clear picture of variation should not divert us from the fact that variation exists, and that the need to take it into account wherever it is noticed and deemed significant.

Current Pracalita-lipi fonts are not always faithful to the culture of handwriting they supposedly represent. This is not unexpected, because most Newars have very limited access to their own literary heritage, especially in manuscript form. There is almost no official support or requirement to use Newar fonts; non-government groups have failed to establish acceptable standards; Indologists’ palaeographical descriptions of Newar manuscripts are habitually impoverished. Consequently, all typographic production is amateur. Moreover, Newar ethnic activists may be interested in playing up differences with ‘Indian’, ‘Tibetan’ and other scribal traditions.

These factors cause Newar fonts to routinely contain forms that are inaccurate, misconceived or exaggerated, and none of them really offers a suitable basis for standardization. An example of a problem is the depiction of kha (NEWAR LETTER KHA) in Rabison Shakya’s Nepal Lipi, which contains an initial upward stroke that differs from Devanagari, but is almost never encountered in Newar handwriting. This looks like difference for difference’s sake.

These factors cause Newar fonts to routinely contain forms that are inaccurate, misconceived or exaggerated, and none of them really offers a suitable basis for standardization. An example of a problem is the depiction of kha (NEWAR LETTER KHA) in Rabison Shakya’s Nepal Lipi, which contains an initial upward stroke that differs from Devanagari, but is almost never encountered in Newar handwriting. This looks like difference for difference’s sake.

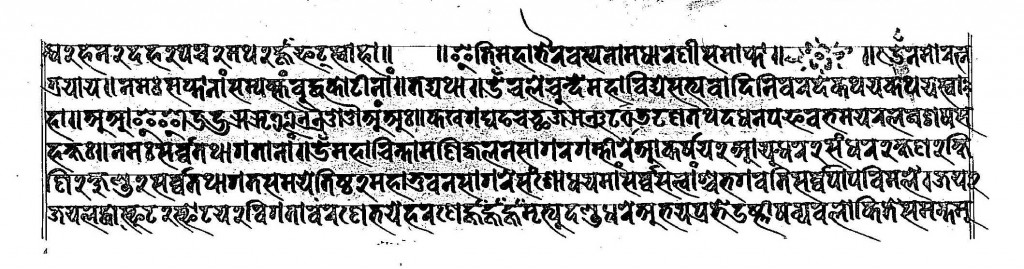

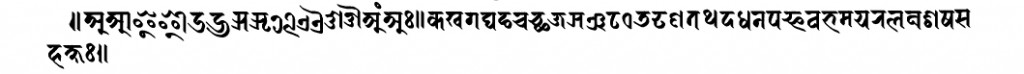

In cases of doubt about which form of a glyph should be adopted as standard, it is recommended that a minimum of one pre-twentieth century manuscript source be consulted, and that the testimony of this source be given priority in the absence of mitigating factors. Helpfully, several manuscripts contain the whole repertoire proposed in N4184. For example, the ālikāli in MS U Tokyo (Matsunami #) 419, dated NS 9(?)12 (=1792 CE), Cintāmaṇidhāraṇī:

The dating of this manuscript can be said to lie at a happy median: it predates the widespread adoption (or rather imposition) of Devanagari in Nepal, and as such is an artifact of a thriving Newar scribal culture; but it is also recent enough that it remains recognisably close to present usage. The in-use repertoire extracted from this sample shows substantial variation from the N4184 repertoire:

Some notable points of variation from N4184 include:

- different ṛ and ṝ ;

- standard headstroke on ga;

- smoothly curved downstroke on ṭa (by far the most common way of writing this character, which improves differentiation from ḍha);

- smoothly curved downstroke on pa (also common);

- the rightward-turning stroke on ma curves up, not down;

- a very common variant form of śa, more like ṇa;

- kṣa has its own slot in the varṇamālā (Perhaps the encoding should allot a point for it, and one for jña, which is also highly distinctive);

- NB: the forms for ba and va are visibly distinct. This is rarely encountered, but is not unknown, as the present example shows.

It is difficult to say, without studying more samples and more historically significant samples, which among the abovementioned forms are preferable. For now I draw attention only to the existence of important variation – there is much more than has been mentioned here – and urge caution in adopting unusual or unrepresentative forms into the standard.

3. Suggested corrections to N4184 repertoire

- § 4.9 ANUSVARA The depiction of this mark in N4184, combining over the middle of the glyph, differs from the manuscript tradition, in which the anusvāra is usually written at the rightmost end of the glyph. (See, e.g. Fig. 4 above, N4184 pp.30, 32 et al.)

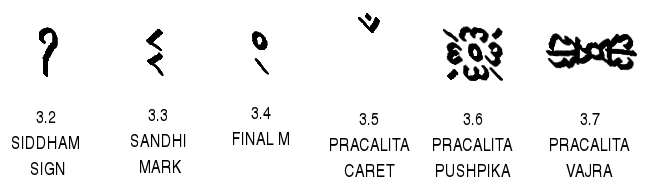

- § 4.11.2 ANJI “This sign represents the Sanskrit invocation siddhir[ ]astu“: This is a form of the sign better known as siddham (see e.g. van Gulik, 1956). I suggest that SIDDHAM SIGN, or an accepted Newar equivalent, would be a better name for this mark than ANJI, which is neither the most accurate term, nor is it emic in Nepal. The Newar term used by Suwarn Vajracharya (N4184:57 fig.35) is “Bhin chin” (= bhiṃ ciṃ). Some marks mentioned in §5.3, “Invocations”, are mere orthographic variants of this mark and do not merit their own code points. The list of symbols by Hemarāja Śākyavaṃśa (prārambha sūcaka – maṅgala cihna N4184:54 Fig.32) shows that this mark is often confused with NEWAR OM and NEWAR SVASTI, from which it must rather be consistently distinguished.

“It represents the aṅkuśa“goad” of the Hindu deity Gaṇeśa”: This interpretation may not be widely accepted; it adds no functional information to the proposal and should be removed.

This mark is also analagous in function, and partly in form, to:

U+1800 MONGOLIAN BIRGA ᠀

U+0FD3 TIBETAN MARK INITIAL BRDA RNYING YIG MGO MDUN MA ࿓ - § 4.13.2 PADA SANDHI MARK “The PADA SANDHI MARK is used in manuscripts for indicating a word break at the end of line”: This mark indicates interruption by any white space (e.g. space for string holes), not only end of line. It is sometimes (rarely) marked both before and after the interruption.

The N4184 name of this mark is unclear. It follows Śākyavaṃśa (N4184:54 Fig.32), but the meaning is a little unclear (foot[note reference], pada? verse, pāda?). In fact, “its function is similar to that of a hyphen”: it is a hyphenation or continuation mark. Suwarn Vajracharya (N4184:57 fig.35) calls it “Khangvo svapu chin” (= khaṅgvaḥ svāpu ciṃ, ‘word connection sign’). Just SANDHI MARK would be a preferable name.

The form of this mark varies widely. The N4184 proposed form, three stacked upward-pointing arrowheads, may not be more common than other attested forms, which include (see, e.g. N4184:54 fig.32): stacked triple dots (like

U+22EE VERTICAL ELLIPSIS ⋮); stacked triple dots and a half-dot; a reverse colon (may be confused with NEWAR FULL STOP); stacked dot, two upward-pointing arrowheads and dot (likeU+1364 ETHIOPIC SEMICOLON ፤), and more. An early form of this mark consists of two left-pointing arrowheads. As the other forms can be regarded as derivative, this early form might be more appropriate for a ‘standard’. - § 4.13.4 FULL STOP “The Newar FULL STOP is used for indicating the end of longer portions of text”: This is not the primary function of this mark. It is usually called a “small m” (e.g. Giunta 2008:188), and its significance is ambiguous or context-dependent. Apparently it derives from m-virāma (personal communication from F. Sferra), which I assume would have been written in proto-Bengali or similar script. In Nepal, however, at a quite early stage, it is used alternatively as final –m, anusvāra (≅

U+0982 BENGALI SIGN ANUSVARA ং), or visarga — sometimes in the same manuscript. This is in fact the same mark as the “Nasal Sign” (§5.1).Later it is (mis-)used as a mark of punctuation like a NEWAR COMMA or NEWAR DANDA and its orthography changes. This is a wholly secondary function (it is not used this way in printed texts), and this should be clarified.

Given the origins of this mark, the standard form should be constructed as a stacked ring (not dot) over diagonal slash, i.e., as shorthand for m + virāma. Its name should be changed from FULL STOP to FINAL M.

[§ 5 Characters Not Proposed]

- §5.4, Editorial Marks (insertion mark): This mark indicates the insertion of interlinear or marginal text. Suwarn Vajracharya (N4184:57 fig.35) calls it “Kaakapada” or “Akhala tophyuchin”; Śākyavaṃśa (N4184:54 fig.32), saṃśodhana saṃketa. Its function is analagous to the Devanagari caret:

U+A8FA DEVANAGARI CARET (U+A8FA)

However, it is more often written with a dot in between the caret’s strokes, like so:

U+1D180 MUSICAL SYMBOL COMBINING MARCATO-STACCATO - §5.5, Ornaments: Few ornaments are consistently used. Among them, the puṣpikā/swāṃ is undoubtedly most frequent. It is analagous to:

U+A8F8 DEVANAGARI SIGN PUSHPIKA ꣸

Suwarn Vajracharya (N4184:57 fig.35) calls this Kvocagu chin (kvacāgū ciṃ?) and represents it flanked by double daṇḍas, which are not integral to the sign. There is a large number of variant forms, as the top four rows and bottom row of Śākyavaṃśa’s chart (N4184:55 Fig.33) shows; these are all variations on the same symbol. Most often it resembles a regular form such as:

U+2749 BALLOON-SPOKED ASTERISK ❉

U+2741 EIGHT PETALLED OUTLINED BLACK FLORETTE ❁ - Also not uncommon in tantric Buddhist texts is the vajra mark, depicted mostly in a horizontal position, in contrast with the Tibetan:

U+0FC5 TIBETAN SYMBOL RDO RJE ࿅

An attested variant form resembles:

U+0FC7 TIBETAN SYMBOL RDO RJE RGYA GRAM ࿇

4. Some characters not mentioned in N4184

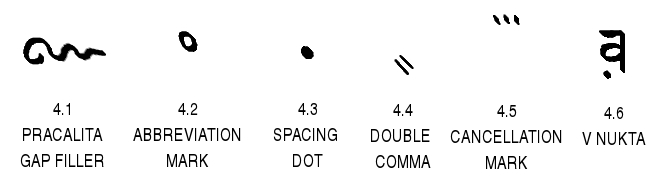

4.1 Space filling mark

This mark is written as a tapering horizontal wave after the end of a sentence, and fills some or all of the line’s remaining white space. Its function is both decorative and as an ‘intentionally left blank’ mark, to indicate (to scribes) that text does not need to be copied into the space. The fifth and sixth rows of Śākyavaṃśa’s chart (N4184:55 Fig.33) seem to confuse it with NEWAR SVASTI. It is analagous to:

U+A8F9 DEVANAGARI GAP FILLER ꣹

U+0E5B THAI CHARACTER KHOMUT ๛

4.2 Abbreviation mark

This mark indicates abbreviation or truncation. It is analagous to:

U+0970 DEVANAGARI ABBREVIATION SIGN ॰

4.3 Spacing dot

An inter-word (sometimes intra-word) spacing marker. It is analagous to:

U+0971 DEVANAGARI HIGH SPACING DOT ॱ

4.4 Double Comma

This mark is functionally similar to NEWAR COMMA, and often interchangeable with it, but it also often appears together with single commas in the same written source, and should be regarded as a distinct mark. Graphically similar to:

U+3003 DITTO MARK 〃

U+301F LOW DOUBLE PRIME QUOTATION MARK 〟

4.5 Cancellation mark

This mark indicates cancellation of a glyph, and is written as a row of dots or thin strokes combined above the character. This convention allows cancellation to be perceived transparently, as deliberate correction, rather than as a smudge, inkblot or other accident. Cancellation is expressed with a minimum of 1.5 such marks over each glyph, to avoid confusion with anusvāra, up to four or five per glyph.

Suwarn Vajracharya calls it Bhinka chin (bhiṃka ciṃ, N4184:57 Fig.35); Śākyavaṃśa (N4184:54 Fig.32) calls it parimārjita saṃketa. It has practically no role in print culture, apart from in the accurate typographic representation of a manuscript or other premodern source. It is functionally similar to:

U+0ECC LAO CANCELLATION MARK

4.6 Newar letter wa (v-nuqtā)

This combination represents the w– sound in Newar. It is more often written in Nepalese Devanagari (so perhaps this could be added to the Devanagari or Devanagari Extended encoding). It corresponds to: U+0935 DEVANAGARI LETTER VA + U+093C DEVANAGARI SIGN NUKTA

4.7 Stress and accent markers

These marks guide pronunciation. The udatta mark is functionally and formally identical to (and therefore may not need encoding in this codeblock) the Devanagari version:

U+0951 COMBINING DEVANAGARI STRESS SIGN UDATTA ॑

The udatta is often accompanied by superscribed numbers. As may be surmised from Suwarn Vajracharya (N4184:57 Fig.35, Akhala hilabulachin = hilābulā ciṃ), two of these figures (COMBINING DIGIT ONE and COMBINING DIGIT TWO) are also used to show that the positions of the glyphs over which they appear should be swapped.

U+A8E0 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT ZERO

U+A8E1 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT ONE

U+A8E2 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT TWO

U+A8E3 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT THREE

U+A8E4 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT FOUR

U+A8E5 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT FIVE

U+A8E6 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT SIX

U+A8E7 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT SEVEN

U+A8E8 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT EIGHT

U+A8E9 COMBINING DEVANAGARI DIGIT NINE

5. On N4184’s other suggested additions

- §5.2, Letter Numerals: Many letter numerals are written as ordinary conjuncts such as pka or pta, and should indeed probably be treated typographically as letters, even if they function in context as numerals. Work needs to be done to determine which letter numerals have genuinely distinctive forms before it can be said that “At least 27 code points should be reserved” (2012:12). In my experience, when letter numerals appear in Pracalita script, they often appear as unaltered imitations of letter numerals in a more archaic script such as Bhujiṅmola or Rañjanā. If this is a common phenomenon, letter numeral code points should probably be allocated to those scripts rather than this one.

- §5.6, Musical Symbols: My impression is that there is too much variation in the depiction of these symbols for them to be usefully standardized; different groups use different, often quite arbitrary, conventions. Since N4184 was able to represent many of them without referring to distinctively Nepalese features, there should not be much need to encode them, either. I suggest that Newar musical symbols should be represented with glyphs from the MATHEMATICAL OPERATORS and other codeblocks unless a case can be made for standardization.

- §5.7, Vowels (proposed VOWEL SIGN AE): It is difficult to standardize a convention that does not yet exist. The purpose of a standard should not, presumably, be to stimulate change. If Newars felt no need for such a character in their long scribal tradition and the print tradition as well, it is hard to see why a standard should impose one. Another reason to not introduce this symbol, apart from the fact that it is not in use and literate Newars are unlikely to recommend that it should be, is that it is not necessary. The example of need put forward by Suwarn Vajracharya (N4184:57 Fig.35), the word ‘Canber[r]a’, can be unproblematically represented as क्यन्बय्र in conventional Newar orthography.

6. Request for comments

Comments will remain open for four weeks from the date of posting. Feedback may also be emailed to the editor at the address given at the top of the page.

— I. Sinclair, 8 February 2012 (Revised: 11 February 2012)

Iain, thank you for taking the time to formulate these comments on the proposal. You raise some important points and offer new issues for further discussion. I have a few brief comments for now and will respond in greater detail later.

1. The form of ‘pracalita’ upon which the proposed encoding is based is the ‘Prachalit Lipi’ standardized and published by the Nepal Lipi Guthi, Kathmandu, 1989. I realize that I forgot to mention this specifically in the proposal.

2. In Figure 4 “In-use repertoire extracted from MS Matsunami 419” you should include the A and AA that precede the I.

3. The glyphs for the conjuncts ‘kṣa’ and ‘jña’ are not to be encoded as independent characters, as per the Unicode encoding model for Indic scripts. These are to be handled at the rendering level, as is done for Devanagari, Bengali, Gujarati, and all other script which use these glyphs; same for ‘tra’, etc.

4. The use of the name ANJI is based upon the graphical and functional similarities between the Newar character and corresponding forms found in Bengali, Tirhuta, Meitei Mayek, Kamarupi (Old Assamese). The name ANJI is used for this character in these scripts, so it is logical to extend the name to the Newar form for purposes of character identity in the UCS.

Kindest regards,

Anshuman

Mr. Pandey, thankyou for your response. To clarify:

1. I was unaware that the Nepal Lipi Guthi’s description was the basis for the proposal. I’m not sure whether we can yet talk about standards for this script (because of difficulties in gauging takeup in the user community, for instance). Although the fact that the Guthi conveys the recommendation of specialists (or ‘enthusiasts’, perhaps) carries some weight, it should be regarded as just one voice, and where it clearly contradicts established convention, disregarded.

2. I omitted the A and AA characters because there are already two examples of A in the sample. At your suggestion, I might correct it to avoid confusion.

3. & 4.: Fine. If this is a preferred convention for naming, I hope it can also be adopted for additions to the N4184 reportoire (as per my proposed names for some of those additions).

Yours respectfully, I. S.

Please find my comments below, number in reference to points in your response above:

1. From what I understand, the Nepal Lipi Guthi put forth a standardized repertoire for the script that was prepared in consultation with several experts, including Pt. Hemraj Shakyavansha. I will investigate the matter.

2. Ah, I see. I did notice the A+ANUSVARA and A+VISARGA at the end of the vowel order, but thought that the A and AA should be shown at the beginning of the order as well.

3. Of course. Uniformity of names across scripts for characters with similar function and shape is a good practice and assists character recognition and implementation.

Below are some additional comments:

4. In reference to your original comment 4.5 (CANCELLATION MARK): I’ve written to members of the Unicode Technical Committee to inquire whether such characters should be encoded on a per-script basis or if they should be encoded in a unified block so as to open their usage across several scripts, as was done for the Vedic Extensions. The CANCELLATION MARK, as well as insertion marks, is not unique to the Prachalit script and is used in Devanagari, Sharada, Siddham, and other manuscripts.

5. In reference to your original comment 4.6 (VA-NUKTA): Letters combined with NUKTA are not considered as independent characters, as per a recent Unicode policy. The preference is to treat them as combined characters. The issue is that there can be a letter/NUKTA pair for each letter in a script, and encoding each of these as independent letters unnecessarily complicates the encoding, as well as collation, etc. It may be sensible to encode a NUKTA for the Prachalit script, which can then be used for representing this VA-NUKTA letter.

6. Do you have examples of the use of the ABBREVIATION SIGN in Prachalit documents?

7. Regarding the position of the ANUSVARA: Ah, I understand. Just for the sake of thoroughness, do you have examples showing ANUSVARA centered above letters?

8. Regarding the FULL STOP / ‘final m’: Do you have examples that show the use of this character for representing this ‘final m’ as opposed to being used as a mark of punctuation?

9. Regarding the combining digits: I’ve asked member of the UTC about encoding such characters on a per-script basis. Hopefully, I will hear back soon.

Best regards,

Anshuman

1. The Nepal Lipi Guthi, if I am not mistaken, is a largely or wholly private organization. It is free to promote a standard, as other organizations are. The extent to which its recommendations function, or should function, as a standard is another matter.

The late Pt. Hemraj Shakya was, I believe, involved with the Guthi’s work (I write this without access to my library). He should rightly be called a specialist – in fact, a professional, since he held a government job as an epigrapher. Some other members of the Guthi likewise were likewise employed, in one way or another, for their ability to read Nepalese scripts.

However, I’m afraid that the personal histories of the Guthi members have very little to do with assessing the accuracy and the uptake of the recommendations they produced. And (although I have no references to hand) Hemraj Shakya’s work has often been called into question by other specialists. I have pointed out at least six important points of difference between N4184 and one documented use of the script, and that is barely a starting point. I regard the standardization of this script in Unicode as an opportunity to correct previous misunderstandings and put forward the best possible standard.

2. Revised.

4. (& 9.) A pan-Indic block for common scribal conventions might be a good idea. Documents that use different scripts within the main text of the document are rare, and it is especially rare (though not unknown, especially where different scribes have contributed) that different scribal conventions are used in the same document.

5. Perhaps it would be useful to encode a Pracalita nukta, as you suggest. Again, that va-nukta is uncommon in Pracalita script, but there is no doubt that it is needed for the transcription of many Newar documents in (some) South Asian script.

6. ABBREVIATION SIGN: I will look for examples.

7. Not many manuscripts in Pracalita script have ANUSVARA written above the centre of the glyph. Those that have are mostly early, and form a very small proportion of the corpus. I’ll post examples later.

8. Small m character: Yes, many examples of each usage I described can be found. The use of this character seems to be so ambiguous that it might be better to avoid any functional description in its name.