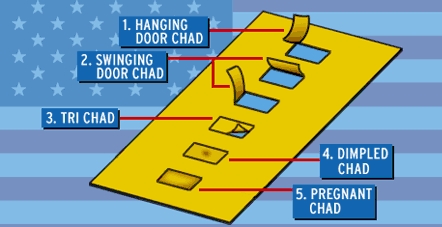

It’s not every day that philology determines the future of a superpower. November 12, 2000 CE, was just such a day. The outcome of the 54th United States presedential election hung in the balance, awaiting a manual recount of the Florida ballots. Officials were shown on television holding up punched ballots to the light, straining to determine whether their chads were dimpled or pregnant, or had hanging or swinging doors.

The officials’ process engendered doubt – doubt that could grow into a grey area which, left unchecked, might obscure entitlement and privilege itself. At this crucial juncture, former Secretary of State James Baker laid down his nation-changing methodological critique:

“How do you divine the intent of the voter on that voting card … with those little punch holes?” he said today on NBC’s Meet the Press. “You’re divining the intent of the voter with respect to whether it has two chads hanging down or whether it’s punched or whether it has an indentation? I mean, that’s crazy.” *

Textual critics were dismissed as diviners; textual criticism became an act of madness. The rest is history. But since history, especially bad history, loves nothing more than to repeat itself, the eve of the 57th presidential election provides an occasion to reflect on the value of philology.

Is philological investigation nothing more than personal opinion, as Mr. Baker implies? In fact, all encounters with text are personal; all texts express problems awaiting resolution, or waiting to happen. To engage critically with a text is merely to deal with it on its own terms. The trade of philologists is in critical editions: text that maximally exposes its own mistrustworthy nature, transmitted with transparent metacommentary on its constitution. One cannot establish confidence in the signal without a mechanism for the identification of noise. So philologists, if they are competent, are simultaneously recoverers of meaning and purveyors of doubt. For the nation-state, that special monopoly that needs nothing if not confidence to survive, such people can be invaluable allies – or implacable enemies.

* Carter M. Yang, ‘Presidency Hinges on Tiny Bits of Paper’. ABCNEWS.com, 12 November 2000.

(Perhaps some had hoped this would be about a completely different episode of philological television, concerning a superpower of another kind – the future kind – and the facsimile editions it claims to be publishing. But I’ll save that for another time.)