宮坂 宥勝 (編集) 『不動信仰事典 (神仏信仰事典シリーズ)』 戎光祥出版 2006

宮坂 宥勝 (編集) 『不動信仰事典 (神仏信仰事典シリーズ)』 戎光祥出版 2006

[Miyasaka, Yushō, ed. Dictionary of the Fudō [Acala] Cult. Kami-butsu shinkō jiten series. ISBN-10: 4900901687. ISBN-13: 978-49009016812006. 434 pp.]

Nepālāvatāra (III): The Paśus that didn’t become Patties

Yesterday, while visiting Kathmandu’s tantric sites with a number of scholars, we ran into a full-scale riot triggered by the cancellation of animal sacrifice. The normal thing to do on this day of the year, the conclusion of Indra Jātrā, is to offer living animals to the Bhairava worshipped in the festival. This year, however, royal patronage has been withdrawn for the first time, so that the government now foots the bill. And the government refused to pay for the traditionally prescribed slaughter. The result: spontaneous rioting, pitched street battles, city-wide disruption and “lockdown” (bandha) now in its second day.

Yesterday, while visiting Kathmandu’s tantric sites with a number of scholars, we ran into a full-scale riot triggered by the cancellation of animal sacrifice. The normal thing to do on this day of the year, the conclusion of Indra Jātrā, is to offer living animals to the Bhairava worshipped in the festival. This year, however, royal patronage has been withdrawn for the first time, so that the government now foots the bill. And the government refused to pay for the traditionally prescribed slaughter. The result: spontaneous rioting, pitched street battles, city-wide disruption and “lockdown” (bandha) now in its second day.

This outcome is not only hard for modern Western minds to comprehend: the Nepalese nouveau elites who incited it had no inkling of what they were stirring up either. Today I heard a non-Newar local sneer, “If the government decided not to kill a chicken, they [Newar traditionalists] would still go crazy!” Actually, what the protesters were objecting to is not so much the loss of animal sacrifice per se, but rather the fact that the festival has not been carried out properly, yathāvidhi.

The fog of misunderstanding is not hard to dispel if one simply recalls how tantric Newar religion is. The idea that bloodthirsty deities must be sated with fresh rakta, found often enough in the tantras and the religious culture of the tantric age, runs particularly deep here. It runs deep enough that one finds it in tantric Buddhist texts too, going back as far as the ‘Indian Period’ of Buddhism.

No news on the 12th-c. Mustang murals

Last year, a team of adventurers were led by a shepherd to caves in a sheer cliff-face in Mustang, where they found and photographed murals dating back to the twelfth century CE. The site, whose location is being kept secret, is apparently affiliated with Tibetan Buddhism, while the murals are clearly the work of Newar artisans. (According to BBC News, with more details in Kantipur Online.)

Last year, a team of adventurers were led by a shepherd to caves in a sheer cliff-face in Mustang, where they found and photographed murals dating back to the twelfth century CE. The site, whose location is being kept secret, is apparently affiliated with Tibetan Buddhism, while the murals are clearly the work of Newar artisans. (According to BBC News, with more details in Kantipur Online.)

Various details reported in connection with this find should be followed up urgently. Particularly, not only “inscriptions” but also “manuscripts” (in Tibetan?) were found this site or at a nearby location. The team announced that these will be translated following their return visit this year.

It does not inspire much confidence that the murals are reported as depicting the “Buddha’s life”, whereas the single image available (shown) actually shows the consort of a tantric siddha rendered in accordance with Newar iconographic conventions — an image which could not fit into any known account of the Buddha’s life.

What would be most beneficial for everyone would be to present full documentation and disclosure of whatever was photographed or taken away from these sites, and make it available to experts working on the history of Nepalese and Tibetan Buddhism. Let us hope that some capable specialist(s), somewhere, is being given access to the team’s findings.

Plea: Could some credentialled person please contact any one of the reported team members — Luigi Fieni (Italy), Broughton Coburn (Wyoming), Peter Athans (USA), Renan Ozturk, or Prakash Darnal (Nepal) — and find out what is going on with this extraordinarily important discovery.

Resolution: PDSz kindly and promptly elicited some useful information from Prof. Charles Ramble. Many thanks to both.

Voting for God

Yesterday the ritual procedure for nominating candidates for the presidency of the United States of America drew to a close. Sen. John McCain’s acceptance speech was littered with references to the consecration of the United States by God:

We believe everyone has something to contribute and deserves the opportunity to reach their God-given potential … We’re all God’s children and we’re all Americans. […]

I’m going to fight to make sure every American has every reason to thank God, as I thank Him: that I’m an American, a proud citizen of the greatest country on earth, and with hard work, strong faith and a little courage, great things are always within our reach.

Frankly, I expected just a little more from John McCain, the self-styled reflective student of history. McCain, unlike his running mate, and the current incumbent (prior to holding office), at least has some personal experience of the wider world — even if it happened to involve pouring munitions from a great height onto civilian infrastructure (for which he can hardly be accused of being unpatriotic).

McCain, in following convention and pushing the buttons of his party’s faithful, neglects to mention what happens to governments that form compacts with Almighty Gods. At some inopportune moment, they disintegrate: inexorably, ignominiously, permanently.

This year Nepal’s monarchy became just the latest in a long line of national elites forsaken by the God(s) integral to their thinking and systems of power. In some respects I am inclined to think that Nepal — where every dinner is a candlelit dinner, thanks to the mismanagement of the country’s meagre resources — not only shows the past, but the way of the future.

When Bhikṣus Attack (I): Killer Zombies, and the Monks Who Send Them

In recent years, Gregory Schopen has done more than anyone to force a reality check on the West’s part-idealized, part-fantasized conception of the Buddhist bhikṣu. Going boldly into vinaya texts that no Buddhist Studies scholar has read before, Schopen finds that the image of monks as world-renouncing ascetics is far removed from the evidence available in these codes.

Monks in India, certainly those affiliated with the Mūlasarvāstivāda, are seen to be entangled with the world as owners, inheritors, and leasers of property; as active seekers of sponsorship for the fabrication of monasteries and images; and as individuals who very much retain their caste and family identities. Rules for performing ‘meditation’ are comparatively thin; in one passage, those who go to the forest to meditate are denigrated as slightly strange in the head. Indian monastics are, in short, anticipated to be doing the things that Newar Buddhists were long accused of doing as “debasements” of monasticism — activities which, we now know, fall within the normal spectrum of behaviour mandated for the Indian tradition.

The most common objection to Schopen’s work has been that the vinaya itself represents an idealization. But this is his very point: it is remarkable that such prescriptions, laden with provisions for a monk’s immersion in mundane business and social affairs, represent the way things are supposed to be done. Nor should these codes be regarded as something which just sit out there in the realm of the ideal: they are indeed binding, written for the purpose of being binding, on their adherents; and in governing the operation of a saṅgha, their word is final.

A contribution published not long ago in the JPTS, by Peter Skilling,* unearths an extreme example of the monk mired in profanity: a ritual for the bhikṣu to magically reanimate a corpse and dispatch it to kill his foe. In the selected passage from the Vinayavibhaṅga (now preserved only in Tibetan and Chinese) the monk is a necromantic performer and would-be murderer by proxy, in a rite that entails:

- the monk going to a charnel ground at a suitable time;

- finding a suitable corpse;

- preparing it with unguents and so on;

- reanimating the corpse by possessing it with a vetāḍa/vetāla spirit,** invoked by means of an (unspecified) mantra;

- sending the zombie off, sword in hand, to kill a named victim, which it does, unless

- the zombie turns on the monk and kills him instead.

As Mr. Skilling observes, with his characteristic good humour and learning (qualities not often found in abundance, much less together, in the Pali Buddhist Studies community), “The primary concern of our text is not the ethics of the matter as such, but what sort of infringements of the monastic rules might be involved” (p.315). If the monk is killed by his own zombie, “the monk incurs a heavy fault (sthūlātyaya)… I do not know whether there are any other cases of posthumous penalties in the monastic codes, but here we have at least one”. That such an outcome was definitely anticipated by the redactors of the vinaya is reflected in the long list of protective techniques provided within the ritual.

Among those defensive options available to the monk is the recitation of a number of “the great apotropaic classics of early Buddhism — notably the Dhvajāgra, the Āṭānāṭīya-, and the Mahāsamāja-sūtras”. Skilling adds, “We still know very little about how the Mahāsūtras were actually used as a set, or to what degree the rituals may have corresponded to [Theravādin rites or] the Rakṣā rituals of Nepal” (p.314). In the literature of Indo-Newar Buddhism there are, in this case as in so many others, more than a few indications to be found regarding the actual practice of such rites.

The Mṛtyuvañcanopadeśa*** of Vāgīśvārakīrti, an Indian master who played an important role in the formation of Newar Buddhism, is a work dealing with the prolongation of one’s life. Although it is concerned primarily with tantric methods such as subtle yoga, it is remarkable that Vāgīśvārakīrti also advocates the recitation of these same Mahāsūtras for the purposes of increasing longevity. This throwback to a much earlier era of monastic practice in a c.11th-century text incidentally marks its author as a monk, or one who at the very least is strongly enculturated in monastic convention.

Later, during the post-Indian period of Newar Buddhism, a number of Sanskrit works were composed on the mollification of life-threatening omens, usually framed as dialogues between Lokeśvara and Tārā. These works offer a kind of meta-protective solution: now one recites either the Pañcarakṣā, or the Mṛtyuvañcanopadeśa itself, in order to avert untimely incidents.

In Skilling’s reference to “the Rakṣā rituals of Nepal”, there is the apparent implication that the rites and literature of the Pañcarakṣā are primarily Nepalese. In fact both the constituent works/deities and the set of five belong to the pan-Indian tradition (the latter, for example, being known to Abhayākaragupta). Again, it would have been nice to see elements regarded as outside the Indian mainstream not being automatically, erroneously, relegated to the Nepalese periphery, where they can be excluded from consideration.

In any case, Peter Skilling’s article adds to the enormous body of scholarship showing that tantric Buddhism has its origins firmly within the monastic community. We do not find a trace of the “siddha” founders proposed by Ronald Davidson in the earliest and best evidence, as exemplified in this extract from the vinaya. Nor should we expect anything different for a tradition that was, right from the start, indeed up to the present, transmitted almost entirely by monks or in connection with monastic institutions, and which makes frequent reference to the practices and ideals of Buddhist monasticism.

* ‘Zombies and Half-Zombies: Mahāsūtras and Other Protective Measures’ The Journal of the Pali Text Society, Vol. XXIX (2007), pp. 313-30.** We should distinguish between the possessing spirit, the vetāla, and the corpse in its possessed/zombified state, as per Somadeva Vasudeva, ‘Concerning vetālas I‘.

*** Johannes Schneider (ed. and tr.), Diss., München, 2006/7? [no details to hand].

Nepālāvatāra (II): I Got Wood

In Kathmandu there are worse places to hang out than in Jana Bahā, majestic home to one of the Valley’s four famed Lokeśvaras. Like many icons of the Valley, it is sacred not only to Newar Buddhists, who control the ritual and institutional complex connected with the deity, but also for Tibetans (as Jo bo dzam gling dkar mo) and a sizeable number of non-Buddhists (in the guise of ‘White Matsyendranātha’).

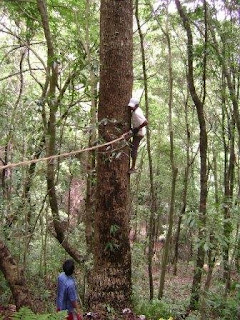

It so happens that tomorrow is an important day in the ongoing renovation of Jana Bahā. Formally this began with expeditions to the nearest forest (vanayātrā) to seek suitable lumber, much along the lines prescribed in Kuladatta’s Kriyāsaṃgraha (itself almost certainly a Newar composition). As almost the entire Valley has been deforested these days, the builders’ Getting of Wood took place on the mountains on the Valley’s rim. Nevertheless, chronicles record that timber was also scarce in the not-too-distant past; it would take several weeks or months to drag the chosen log(s) to their destination in the city.

It so happens that tomorrow is an important day in the ongoing renovation of Jana Bahā. Formally this began with expeditions to the nearest forest (vanayātrā) to seek suitable lumber, much along the lines prescribed in Kuladatta’s Kriyāsaṃgraha (itself almost certainly a Newar composition). As almost the entire Valley has been deforested these days, the builders’ Getting of Wood took place on the mountains on the Valley’s rim. Nevertheless, chronicles record that timber was also scarce in the not-too-distant past; it would take several weeks or months to drag the chosen log(s) to their destination in the city.

What makes this renovation qualitatively different from its many predecessors in the Newar tradition is a new level of transparency. The organizers have taken the startling but commendable step of documenting much of the process online, in English, at janabahaa.blogspot.com.

Nuggets of Untruth (I): Ron Davidson on Indian Esoteric Buddhism

Recently, a friend and scholar of tantric Buddhism asked me for comments on the following statement by Ronald Davidson, from ‘An Introduction to the Standards of Scriptural Authenticity in Indian Buddhism’:

Mantrayāna, developing as a system from the seventh century on, received no serious challenge from the Buddhist community in India.

Being a bit tied up at the moment, I could only answer in brief; and of course, those Vajrayāna traditions that were wiped out by Theravādins in Sri Lanka and Thailand have no living representatives there who can answer. Meanwhile, comments are open. Discuss!

Āryatārā Totally Looks Like Vanaratna's Wife

A magnificent Indian manuscript illumination of Tārā, purchased seven years ago by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, bears a striking resemblance to the well-known Newar painting of Vanaratna’s wife giving dāna to various Buddhist and non-Buddhist ascetics.* This further bolsters a claim by Dina Bangdel that the main figure in the latter work was depicted as Vanaratna’s favourite form of Tārā — a notion which could have used a lot more support when it was first proposed.

(However the suggestion that the event depicted is an “Abhishekha (Initiation)”, as is unfortunately recorded in LACMA’s catalogue, is quite without foundation; rather it is evidently a samyak, namely, a saṅghabhojana offered to all the monasteries of a district on some auspicious occasion — in this case, the first-year anniversary of Vanaratna’s parinirvāṇa.)

* References, etc. (including an explanation of what the famed sthavira was doing with a ‘wife’) are to be found in my [unpublished] review of Circle of Bliss.

Not submitted to totallylookslike.com.

I'm back.

Because it looks like I’m going to have to be.

Eda, ‘Untersuchung zur Nāgārjunas Ratnāvalī’ (2005)

Eda, Akimichi. ‘Untersuchung zur Nāgārjunas Ratnāvalī unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Kommentars des Rgyal tshab (Investigation on Nāgārjuna’s Ratnāvalī and the comment of Rgyal tshab)’. Diss.: Fachbereich Fremdsprachliche Philologien, Universität Marburg,

2005.

PDF: via http://archiv.ub.uni-marburg.de/diss/z2007/0199/.