Emmanuel Francis. 2018. ‘Indian Copper-Plate Grants: Inscriptions or Documents?’ In Alessandro Bausi, Christian Brockmann, Michael Friedrich, Sabine Kienitz (eds.) Manuscripts and Archives: Comparative Views on Record-Keeping. Studies in Manuscript Cultures 11. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 387–417. ISBN: 9783110541397. DOI: 10.1515/9783110541397-014 [chapter]. [PDF 🔓]

Asian Iconographic Resources Information Platform

Mori, Masahide 森雅秀. 2017. AIRIP: Asian Iconographic Resources Information Platform「アジア図像集成 情報プラットフォーム」. http://air-p.jp/.

author: Kanazawa U; researchmap.jp.

Updated: 2017/8; an extension of, and formerly noticed under: Asian Iconographic Resources アジア図像集成, http://air.w3.kanazawa-u.ac.jp (also: PDF listings of the Tibetan 500- and 360-deity pantheons).

Bühnemann (2017), Vāruṇī in Nepal

Bühnemann, Gudrun. 2017. ‘Churned from the Milk Ocean, Invoked into a Skull-Cup: The Goddess Vāruṇī in Nepal’. Berliner Indologische Studien/Berlin Indological Studies 23 pp. 215–264. [academia.edu]

Sree Padma, ‘Hariti: Buddhist Elaborations, Saivite Accommodations’ (2011)

Sree Padma. ‘Hariti: Village Origins, Buddhist Elaborations and Saivite Accommodations’. Asian and African Area Studies (『アジア・アフリカ地域研究』), 11 (1), 2011, pp.1–17. [PDF]

Book of the Year: ‘Hardships and Downfall of Buddhism’

Giovanni Verardi (appendices by Federica Barba). Hardships and Downfall of Buddhism in India. Nalanda-Sriwijaya Series 4. Delhi/Singapore: Manohar & Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2011. 523 pp.

Not a very catchy title, but I doubt that something more direct (say, The Hindu Extermination of Buddhism) would have been very appealing to Singapore’s Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, the book’s publisher.

This book is an extraordinary achievement, all the more so for it relying only indirectly, for the most part, on scriptural and epigraphic sources. Verardi’s contribution is based on something at least as useful: first-hand observation of the key sites and remains, clearly articulated in terms of long-term patterns. It is by far one of the most important contributions to the study of Buddhism in India published in a long time — though I don’t agree with everything in it, by any means. (Given the chance, I will expand on that later.) The omission of any discussion of the Theravādins’ catastrophic role, painstakingly explained in Peter Schalk’s 2002 Buddhism among Tamils volumes, has to be regarded as particularly puzzling — at least until one sees Peter Skilling’s name in the acknowledgements. But let me be clear: Verardi, who has pursued his line of inquiry for over three decades, has succeeded in making sense out of a slew of data in a way that is unlikely to be bettered for some time.

Li, ‘The 13th-century monk U rgyan pa Rin chen dpal’ (2011)

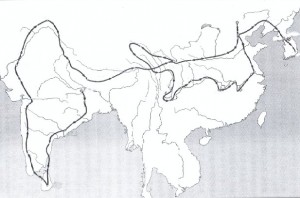

Brenda W. L. Li. ‘A critical study of the life of the 13th-century Tibetan monk U rgyan pa Rin chen dpal based on his biographies’. D.Phil dissertation, Oxford University. 2011. [official site]

From the Abstract

U rgyan pa Rin chen dpal (1230–1309) was a great adept of the bKa’ brgyud school of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly renowned for his knowledge of the Kālacakra tantra and the unique teaching known as the Approach and Attainment of the Three Vajras (rDo rje gsum gyi bsnyen sgrub), said to have been given to him in his vision by Vajrayoginī (rDo rje rnal ‘byor ma) in the Miraculous Land (sprul pa’i zhing) of U rgyan. He was the student of the 2nd Karma pa, who entrusted him with the Black Hat, which he passed to the 3rd Karma pa. He was also a great traveller who journeyed widely across and beyond Tibet. He met Qubilai Khan in the capital of Yuan China and visited sacred Buddhist sites in South India. He has been aptly described by van der Kuijp as “the great Tibetan yogi, thaumaturge, scholar, alchemist, and traveler”.

Thanks to the availability of a large amount of hitherto unknown materials from eleven biographies, the thesis has put considerable weight on the bibliographical comparison and analysis of the different works in an attempt to establish the possible relationship between them.

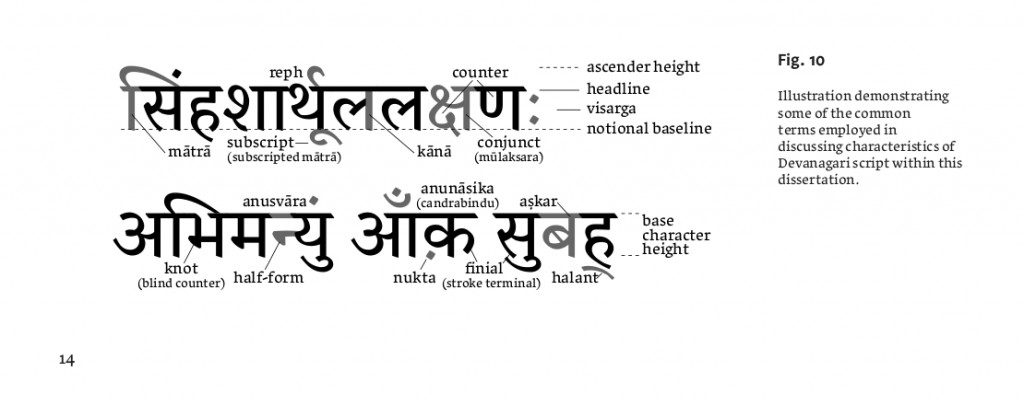

Hunt, ‘Considerations for Devanagari Typography’ (2008)

Paul D. Hunt. ‘Language and region specific considerations for Devanagari typography. Case studies in Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi, & Nepali’. M.A. Thesis, University of Reading, September 2008. [PDF]

Reading, England, produces more than just atheist comedians; the University of Reading also awards respected higher degrees in Typeface Design. Hunt’s M.A. thesis, set in elegant Grandia, explores a few of the varied functions that Nāgarī type may be called on perform. It’s potentially useful reading for those working on Sanskrit texts who have dreamed of a better Unicode typeface, and who seek the typographical vocabulary to articulate exactly what they are looking for.

The current situation is far from perfect, of course. Of the Unicode Nāgarī faces out there at the moment, I could only recommend two or three, at most, for serious philological typesetting. It is frustrating that adequate faces are not even available to buy, for the most part.

Continue reading “Hunt, ‘Considerations for Devanagari Typography’ (2008)”

Dziwenka, ‘Last Light of Indian Buddhism’ (2010)

Ronald James Dziwenka. ‘The Last Light of Indian Buddhism’ — The Monk Zhikong in 14th Century China and Korea. PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2010. 406 pp. UMI Number: 3412160. [Thanks to A. M.]

Abstract

dissemination and reception of his thought and soteriological paradigm of practice from his native state of Magadha, then Sri Lanka, and then throughout India, Yuan China and Goryeo Korea. The other is [to] explicate the main elements and concepts of his thought and present them to the academic community.

Läänemets, ‘The Gaṇḍavyūha as Historical Source’ (2009)

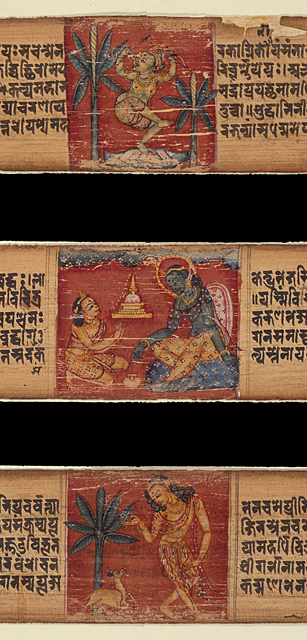

Märt Läänemets. ‘Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra kui ajalooallikas (The Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra as a Historical Source)’. Dissertationes Historiae Universitatis Tartuensis 17. PhD diss., Tartu University, 2009. 281 pp. [abstract / PDF]

Läänemets’ dissertation, written in Estonian, also comes with a detailed English summary (pp.263‒274).

Allow me to briefly take up a couple of points mentioned in the summary. Firstly, it is surprising that the writer concludes that the Gv was composed in Central Asia “on the basis of extra-textual historical facts”, even though it is pointed out that the action takes place almost entirely in identifiable sites in South India (p.269).

Secondly, it is stated that the “Gv reached Nepal… no later than the middle of the 12th century, but likely a century or two earlier” (p.268). Here Läänemets refers to an MS dated ~1166 CE, which he describes as the oldest and “only [this must be a typo] extant text”. There is no reason to think that the Gv was not circulating in Nepal in approximately the same period that it began to circulate in the rest of South Asia, even if very few palmleaf MSS have survived. For instance, Kamalaśīla, who prescribes the recitation of the Bhadracārī (which was attached to the Gv by Kamalaśīla’s time, the late eighth century) as part of a bodhisattva’s routine in his first Bhāvanākrama, is said to have resided in Nepal, where such texts were presumably already well known.

One Nepalese MS which is not mentioned is an illustrated palmleaf codex, preserved in just a few folios across two collections in the United States: at LACMA [see right; link], and Brooklyn Museum [link]. Although the folios at LACMA have been studied by the inimitable Dr. Gautam V. Vajracharya, I do not know whether these two remarkable leaves have been identified as constitutents of the same codex, as they manifestly appear to be.

Hannotte, ‘Sadyojyoti’ (1987); Borody, ‘Bhogakārikā’ (1988)

Two dissertations on the eighth-century Śaiva author Sadyojyoti, both supervised by Krishna Sivaraman, have recently become available online at McMaster University:

Leon E. Hannotte. Philosophy of God in Kashmir Śaiva Dualism: Sadyojyoti and His Commentators. PhD Diss., McMaster University, 1987. Open Dissertations and Theses, Paper 2089. [abstract & pdf]

Wayne Andrew Borody. The Doctrine of Empirical Consciousness in the Bhoga Kārikā. PhD Diss., McMaster University, 1988. Open Dissertations and Theses, Paper 2073. [abstract & PDF]

For students of late Indian Buddhism, Sadyojyoti is a person of interest, given his advocacy of epistemes such as the sākārajñānavāda / nirākārajñānavāda dyad, which was already known to Kamalaśīla, as well as to some later Buddhist authors.

Hannotte’s dissertation was published by the National Library of Canada in 1989, and as F. S. kindly pointed out to me, Borody’s dissertation finally came out with Motilal Banarsidass in 2005. Nonetheless, it is handy to be able to freely access both dissertations.