Refer to: Anshuman Pandey, ‘N4184 Proposal to Encode the Newar Script in ISO/IEC 10646’, February 29, 2012 [PDF]. Previous discussion: here.

0. On the Name ‘Newar’

The name ‘Newar’ is preferable simply because most other options can be ruled out. ‘Nepalese’ is untenable, because it falsely implies a one-to-one relationship with the present-day nation-state, even though it is accurate within a certain (historically earlier) context. ‘Newari’ is a (now deprecated) name for the language – not the script, nor anything else; ‘Nevārī’ is quite meaningless, except to some Indologists.

The proposal, as I understand it, indeed deals with the Pracalita script, but has enough hooks to allow unification with proposals for other Newar scripts, such as Bhujiṅmola – hence ‘Newar’. (NB: It is not yet clear whether unification with Rañjanā – which is, strictly speaking, Indo-Nepalese, and which has a user base that includes many non-Newars, such as Tibetans – is feasible. In any case, much of the present and previous discussion about the Pracalita script is also applicable to Rañjanā.)

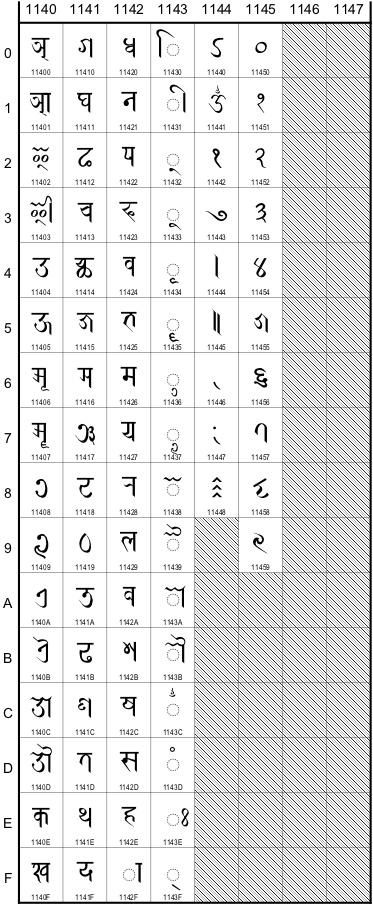

1. Additional Information On Glyph Names

11442 NEWAR FINAL ANUSVARA: Although this mark originates with the m-virāma mark used by East Indian scribes, in Nepal it has multivalent significance and in many contexts has nothing to do with nasalization (often being interchangeable with 1144B NEWAR GAP FILLER). Recommendation: Minimise phonetic/semantic description in favour of graphic description – maybe NEWAR SEMICOLON for want of a better term. Classify under Punctuation or Various Signs.

11443 NEWAR SIDDHI = शुभचिं (Shrestha NS 1132:21). There is no uniform name for this mark in Newar (esp. not the neologism bhiṃciṃ), nor is siddhi/añji recommended (not just because this designation is unknown in Nepal, but because usage may also vary; confusion with NEWAR OM is common). Recommendation: NEWAR AUSPICIOUSNESS MARK or similar.

11448 NEWAR COMMA = अर्धविराम (Shrestha NS 1132:24).

11449 NEWAR DOUBLE COMMA: I now think this mark can be represented with two adjacent NEWAR COMMAs. Its usual behaviour of stacking diagonally (see Fig.3) rather than horizontally should however be specified. Recommendation: Remove from the repertoire.

1144B NEWAR HIGH SPACING DOT = अल्पविराम (ibid.).

1144C NEWAR ABBREVIATION SIGN CIRCLE = संक्षेपीकरण यानाः च्वयातःगु थासय् थुगु चिं (ibid.).

1145A NEWAR FLOWER = स्वांथें ज्याःगु चिं (ibid.).

1145C NEWAR PLACEHOLDER MARK is the line-width equivalent of the NEWAR GAP FILLER (see below). Recommendation: Change name to NEWAR LINE FILLER MARK.

2. Morphology of the Gap Filler Mark

Following comments on earlier drafts of N4184, especially those of Kashinath Tamot, it should be clarified that the primary function of 1144B NEWAR GAP FILLER is not that of indicating a break in a word (as per the previous name SANDHI MARK), but rather of filling space up to the end of a line margin. (A hyphen indeed performs a space-filling operation as well as functioning as a word-breaking mark. However, I suggest that ‘hyphenation’ be dropped from the formal description of this mark to avoid confusion.)

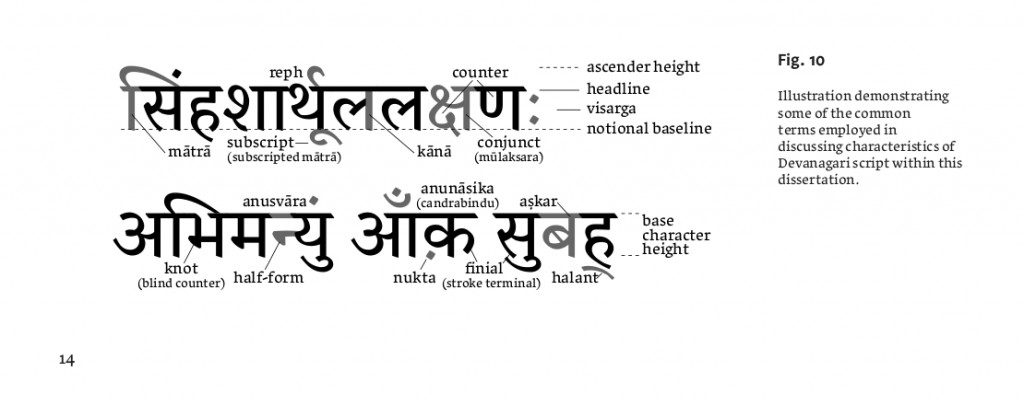

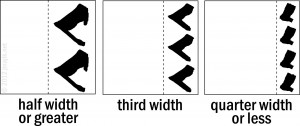

The purpose of this mark has been obvious enough to specialists – recently see, e.g. Ishida (2011:ix), where it is called a ‘line-filler character’, Zeilenfüllzeichen. (In fact, this mark does not fill a line – this is the function of 1145C NEWAR PLACEHOLDER MARK; rather, it fills a space of less than one full glyph-width at the end of a margin, not necessarily the end of a line.) Nonetheless, it is easily seen that the mark could be confused with, e.g., a visarga, daṇḍa or similar. In earlier discussion on the proposal, its purpose has remained unclear to the user community, perhaps due to its unstable shape. Significantly, the NEWAR GAP FILLER MARK changes according to the width of the glyph. Its behaviour may be represented as follows:

Variations in this mark may therefore be regarded as contextual alternatives, rather than separate code points. I suggest, as per the diagram, that no more than three variants need be represented; although the glyph could conceivably incorporate four or more variations (e.g., five vertically stacked dots, at 20% character width), this is probably excessive.

Recommendation: It may be implemented as one code point with contextual alternates, or 3 or more code points corresponding to each quantum of width.

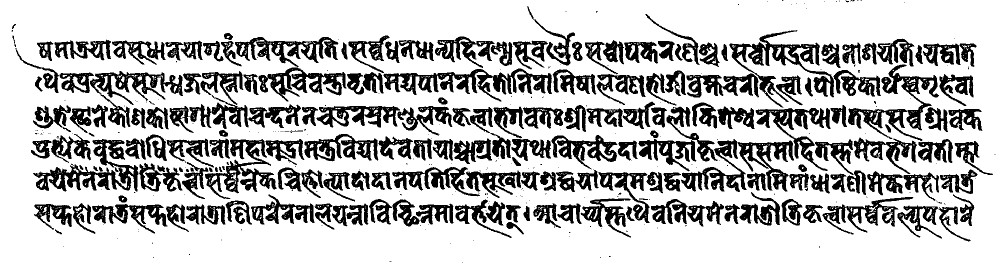

3. Swash Forms

Several glyphs may be alternatively represented with swash forms, created by extending elements of the glyph into surrounding white space. These forms do not require dedicated representation in an encoded repertoire; however, they should be included in any full description of Indo-Newar scribal culture, and font designers might want to incorporate them. Swash forms are often contextually invoked: they are used at the top line of a block of text (upward extension), but may also be seen on the bottom line (downward extension), and even more rarely at the right and left margins, and within interlinear white space. An example:

Characters routinely represented as swash forms include:

11432 NEWAR VOWEL SIGN U, 11433 NEWAR VOWEL SIGN UU, 11439 NEWAR VOWEL SIGN AI, 1143B NEWAR VOWEL SIGN AU, (superscribed)11428 NEWAR LETTER RA, 1143D NEWAR SIGN CANDRABINDU, 1143E NEWAR SIGN ANUSVARA– upward extension;11402 NEWAR LETTER I, 11403 NEWAR LETTER II,(subscribed)11417 NEWAR LETTER NYA, 1141D NEWAR LETTER TA, 11423 NEWAR LETTER PHA, 11425 NEWAR LETTER BHA, 11429 NEWAR LETTER LA, 1142D NEWAR LETTER SA, 1142E NEWAR LETTER HA, 1143C NEWAR SIGN VIRAMA– downward extension.

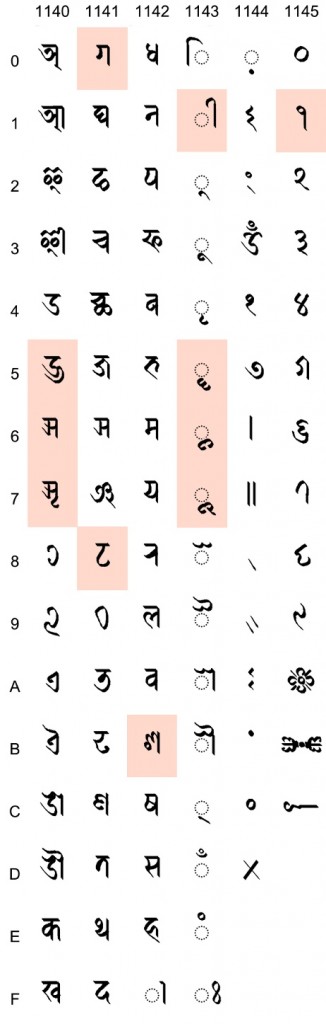

4. Revisions To Standard Forms

The following changes to standard forms are recommended – see glyphs highlighted in Fig.3, in which all glyphs have been redrawn from scratch to accord with common scribal practice. The most widespread change is that the headstroke no longer extends past the right descender (which is inconsistent with almost all scribal practice). Standard forms for VOCALIC R, VOCALIC RR, GA, SHA, dependent VOWEL SIGN II, VOCALIC R, VOCALIC RR as well as *VOCALIC L, VOCALIC LL (these should certainly be specified and named) should be altered accordingly. DIGIT ONE should also be changed in order to avoid confusion with SIDDHI.

5. Some Remaining Questions

5.2 Letter-Numerals: “There are at least 27 such Newar ‘letter numerals’… It may be possible to unify Newar letter-numbers with corresponding Brahmi characters.” The issue here, as far as I can see, is: which letter-numeral conjuncts differ from non-numeral conjuncts of the same letters (all differences should be specified). To put it another way: which letter-numeral conjuncts uniquely signify letter numerals, if any? Perhaps our European colleagues, with their extensive access to funding, institutional support and manuscript sources, could clarify the matter. (Don’t worry, we won’t hold our breath.)

5.3 “Should editorial marks be encoded on a per script basis or would be it reasonable to unify such marks in a pan-Indic block?” (Pandey 2012:13). Out of our hands, but if they aren’t unified, they should be included in the Newar block.

[rev 0.1: 2012/06/19]